In September 2017, Fuji TV revived an old comedy character originally created in the 1980s by the comedy duo Tunnels. The character was Homooda Homoo, an effeminate man with pink cheeks who used feminine suffixes when talking about himself, often with a full-on lisp. He essentially embodied every homosexual stereotype ever while being called the Japanese equivalent of “Gay McGay,” which was apparently what made him funny. No, really, the entire gag about Homooda was that, occasionally, someone would turn to him and accusatorily ask “Are you a homo?” That’s it.

The reactions to the character’s revival were frigid, to say the least. To be clear, there was no outrage or anything like that around the country. It was more of a prolonged sigh followed by a facepalm and people asking, “Why are we still putting stuff like that on TV?” In a series of street interviews conducted by Yahoo! on the subject of Homooda, most of the surveyed young people felt the character just wasn’t suited for modern Japan. While some admitted to laughing at his antics, they acknowledged the portrayal was offensive to gay men, and that, in many ways, it was an embarrassment to the country.

The president of Fuji TV ended up apologizing for reviving Homooda Homoo, and almost as if to make up for it, in January 2018, the station aired the Tonari no Kazoku wa Aoku Mieru series, which portrayed male homosexuality in a much more dignified fashion. The show, the name of which loosely translates as “The family is always greener on the other side” and is occasionally known in foreign markets as Residential Complex, tells the story of four families living in a “cooperative house” complex. The details of their living arrangements are unimportant. What’s important is that one of the couples, Wataru and Saku, are gay.

A scene from Residential Complex

For many Japanese people, this was one of the first homosexual partnerships they’ve seen on TV in a long time. It’s important to note that Wataru and Saku aren’t the stars of the show, but their stories often cross with the series’ main plotlines, in effect putting a spotlight on them and their relationship. So, what exactly is their relationship then?

For one, it’s not perfect. The slightly older Wataru is deeply in the closet and actually introduces his boyfriend Saku to the rest of the families in the complex as his nephew. Wataru’s fear of coming out is so great that, for most of the series, he also strings a female acquaintance along (while knowing full well that she’s in love with him) as a form of social camouflage. Saku cannot abide by this, but when confronted about it, Wataru explains that it’s hard for him to change and that he is afraid. This happens midway through the show, and it’s when the show really hits its stride.

Wataru’s admission of fear and being unable to change are all feelings most likely shared by Japan’s older generation. The younger people of Japan don’t really need to be convinced that gay men are just like everyone else. They’re modern, they have the Internet, and, as demonstrated by the Yahoo! interviews, they know what’s up. Older people might have a harder time of it, but as Wataru starts being more forthcoming about his homosexuality, perhaps the show’s more senior viewers will also start to challenge their previously held beliefs. That certainly seems to be the show’s intent.

Near the end of the show, Wataru and Saku become an openly gay couple, and they even get the tentative blessing of Wataru’s conservative mother. Now, it’s true that their main story arc is focusing primarily on their homosexuality, which might not be ideal. In a perfect world, the characters would just be gay and go about their everyday lives, without anyone having to bring attention to their homosexuality. But we aren’t living in a perfect world, especially if you’re part of the LGBT community in Japan.

Japan still offers little legal protection against discrimination for LGBT people. That said, progress has been made. LGBT partnerships are now legal in Sapporo, Fukuoka, and Shibuya, with more cities and wards looking to follow suit. And if the Japanese Red Cross is successful, perhaps this year Japan will stop banning gay men from donating blood for up to one year after they’ve had sex. Finally, we might also see more Japanese TV shows featuring genuine, non-comedic gay characters.

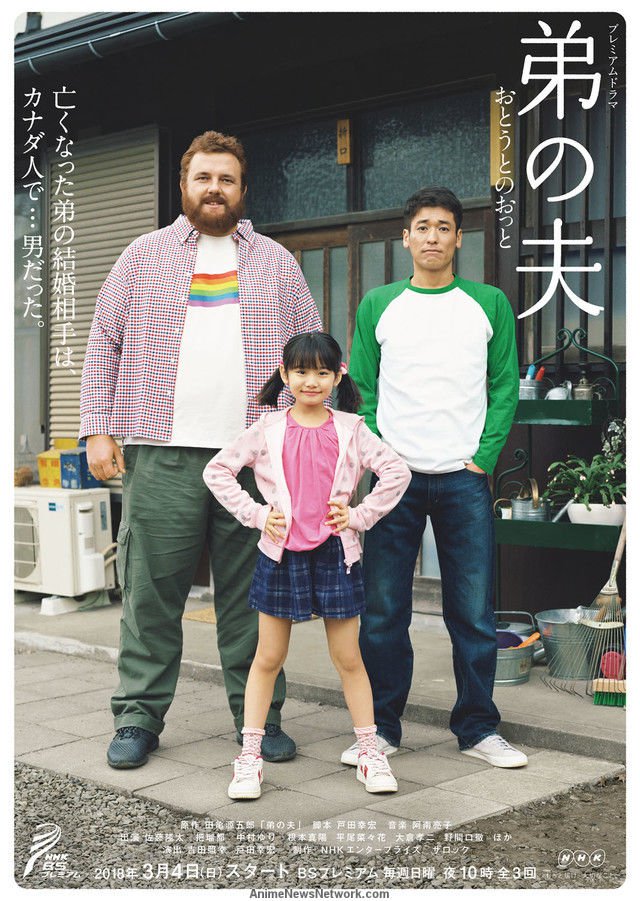

For better or worse, TV does influence how we see the world, so what Japan needs right now is better representation of the LGBT community in its popular entertainment. Tonari no Kazoku was a good start, and the rest of 2018 so far has been similarly significant. Just this March, NHK broadcasted three episodes of My Brother’s Husband, a story about a Canadian man visiting his deceased husband’s twin brother in Japan, starring the former sumo champion Baruto Kaito. Will this trend continue in the future? We can only hope so.

Promotional poster for My Brother’s Husband